[by Shannon Roberts]

Confession: When I first started writing, I copied.

Not ideas—not consciously anyway—but voice

Initially I modeled my work after one of my (at the time) favorite bloggers and web-comic writers, Jerry Holkins. I started to fold in some Terry Pratchett and I sampled from Robert Heinlein. Whenever I came across a technique I liked, I tried to emulate it, until one day I looked at my work and I realized I was no longer copying. I could still spot the influence of my favorite authors, but somehow, at some point I couldn’t quite pin down, my work had developed its own flavor.

I was writing with voice. My own voice.

I always tell authors that there are two ways to improve their craft: writing and reading. The first is understandable—after all, practice makes perfect. Yet many authors get so caught up in their own work they forgot to stop, rest, and pick up a book. A writer who doesn’t read is like a deaf musician; at best, you’ll only ever appreciate the medium from a technical perspective.

I would love to tell you that it doesn’t matter what you read—that as long as you DO read, as much as possible and as often as possible, your writer’s voice grows stronger and more sophisticated by the day. That isn’t quite true. It’s important not only to read, but to read a variety of work. If a fantasy author only ever reads fantasy, his voice and style will be bound the by conventions of the genre. If a mystery writer only ever reads mysteries, his work will devolve into whodunit clichés.

Of course quality, not simply variety, is important. There’s nothing wrong with pop fiction—it’s popular for a reason—but there’s a reason certain novels stand out. There’s a reason you know the opening line of Moby Dick, even if you haven’t read it. Literature, it turns out, is important.

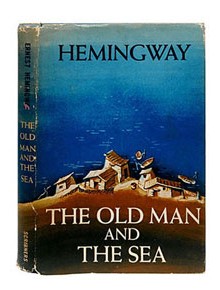

When I read The Old Man and the Sea for the first time, I fell in love. I was struck by its economy of language, the sleek, lean passages without an ounce of unnecessary narration. Clearly I’ve moved away from that over time, but back then, I was so fired up that I wrote an entire manuscript under its influence. It was not a bad manuscript, but I wouldn’t call it good—it was just spare, far too minimalist. Those short, cutting lines I longed for lost all their impact because the story was built of nothing BUT short, cutting lines. It was time to expand my writer’s toolbox—so I turned to more substantial offerings, and found that when I surrounded a clipped, tight line with longer, richer sentences, the whole work was more rounded, the style more sophisticated.

So you’re reading, you’re writing, you forced yourself out of your comfort zone and finally read Ulysses (or whatever it is you might have been dreading).

You’re well on your way to developing a stronger voice, one that (hopefully) reaches out, grabs a reader by the lapels, and makes them pay attention. What’s left?

Read poetry—better yet, write some.

Some poetic forms are more structured than others, but I suggest you sample them all—because it takes skill to write within a particular format, and the discipline it fosters will serve you well as a writer. I was skeptical when told this, but a friend of mine who happens to be an excellent writer swears by it.

Of course, not all of us are built to write sonnets, and when I sat down to whip out a couple (I know, I know), it went about like you’d expect, with ground teeth and too many cups of coffee and a final declaration that this was, after all, a stupid exercise.

“So try something else,” my friend said.

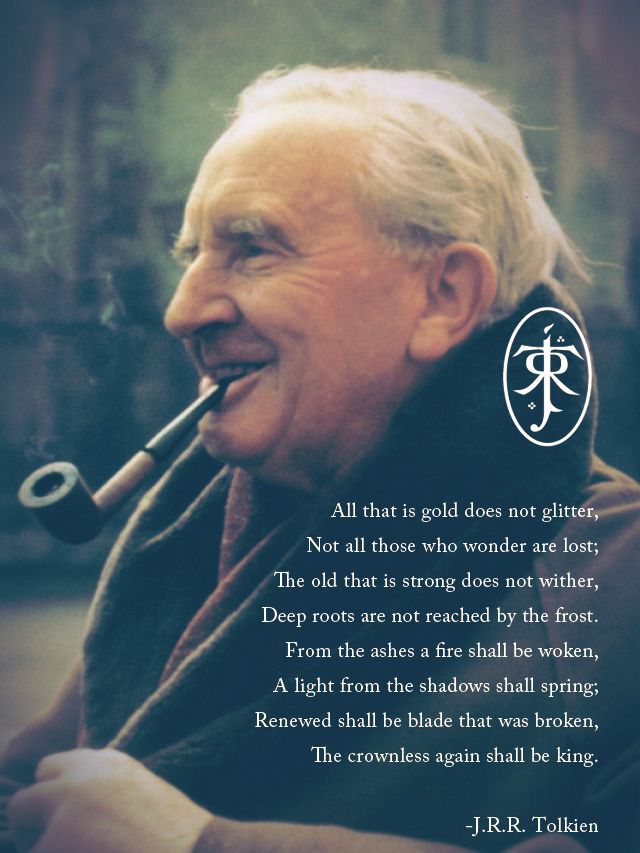

I read Leonard Cohen, Kevin Young, Lord Byron. I liked some of it, but I didn’t care for most of it. It was only on revisiting Tolkien and some of his alliterative poetry that I found a structure I not only cared about, but adored. I went mad for alliterative poetry, and to my surprise, my friend was right. Not only did I learn to incorporate that beautiful, rolling rhythm into my prose, it taught me how to pick and choose my words, how to pack a lot of feeling into a few lines.

So read and write, narrative prose and poetry. Experiment. The more material you process and produce, the bigger your toolbox—your vocabulary, your understanding, your experience—becomes.

Interested in getting professional guidance in developing your unique writing voice? We have editors who can do everything from coaching you in writing craft to improving specific elements of your manuscript. Please contact Ross Browne at the Tucson Office for more information.