[by John Robert Marlow]

So you want your book to be a movie. (Or series.) Who doesn’t, right? Most authors dream about this, but few do more than cross their fingers and hope Hollywood will come knocking. And, hey, sometimes that happens. Usually after the book (or book series) has become hugely successful in its own right, thus drawing Hollywood’s attention. Because in the same way that sharks are drawn to blood, Hollywood is drawn to money. But…

Hollywood is also drawn to potential money. Picking up the rights to Harry Potter is an expensive proposition. Picking up the rights to the next Harry Potter, before it’s widely recognized as such—not so much. Which makes Hollywood wide open to finding that Next Big Thing, before it’s the Next Big Thing. And, keep in mind, Hollywood’s idea of bargain-shopping is not your idea of bargain-shopping. If the Next Big Thing costs them a couple of million, that is (to them) Dollar Store pricing. Unlike, say, the $450 million Netflix recently shelled out to screenwriter Rian Johnson for two sequels to his Knives Out feature. (Yes, you read that right.)

The catch is, they have to know that you and your book exist. Now, maybe a helpful bookstore employee will recommend your out-of-print book to an A-list screenwriter who happens to be browsing the shelves for something to read (which is how Limitless ultimately got made). But probably not. All things considered, a more proactive approach would seem the wiser choice. Here’s a brief primer on some basic decisions you’ll need to make to get the cameras rolling…

Book Rights or Screenplay

You can approach Hollywood with book rights alone, or with a full-blown feature screenplay or series proposal. Absent runaway bestseller status, book rights aren’t likely to sell for a whole lot of money. This is because books raise questions screenplays don’t. Among them: How do we turn this 300-page book into a 120-page screenplay? Half the book takes place inside the hero’s head; how do we fix that? This would cost $300 million to shoot—can we make it less expensive? Can we tell this story in three acts, streamline the plot, strengthen the character arcs? If we buy the rights, who do we hire to adapt? What’s that going to cost? How long will it take? And, at the end of that process—will we have a screenplay we like?

On the other hand, when you walk in the door with a finished screenplay, all of these questions have already been answered. They like it or they don’t. If they like it, they buy it. Done deal. They don’t even have to read the book. So now you’re most likely talking a purchase price in the mid-six figure range, minimum. Whereas rights alone are more likely to start at low-four, with option (for less than that) more likely than immediate purchase. Should you choose to go for the gold, so to speak, and create an adapted screenplay, there are several routes to the finish line. But first, let’s take a look at the overall pros and cons of screenplays in general…

Pros

Crazy Money: Screenplays from first-timers generally sell for $300-$600k, with (typically) one or more per year selling north of $1M. The record-highs for first-time sales are $5.6M (co-written with a veteran screenwriter) and $3.2M (written alone). First-time novels, on the other hand, typically fetch advances of $10k and under.

You Still Own the Book Rights: Publishers nowadays try to glom onto your movie rights. Sometimes with a movie-rights clause, sometimes with the less-obvious “Derivative Rights” clause. Hollywood cares very much about movie, series, video game, theme park and merchandising rights. But, by and large, they really don’t care about your book rights. There’s even a standard contract clause that covers this, called “Separation of Rights.” Which says you get to keep the book rights. This is extremely important, because…

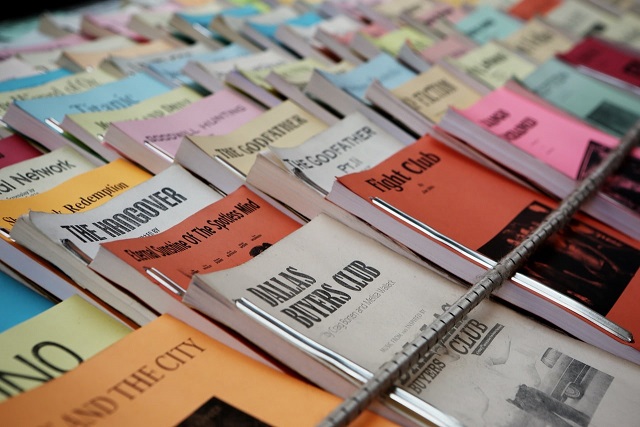

Hit Movies and Series Sell Tons of Books: Literally. Tons. Of. Books. While writing Make Your Book A Movie, I spoke with authors whose books were out of print shortly before the movie came out (Alan Glynn; Limitless), authors whose books were already selling in dozens of languages (Vikas Swarup; Slumdog Millionaire), and everyone in between. Without exception, sales skyrocketed after the movies hit. This matters more than one might think, because whatever Hollywood pays you is whatever Hollywood pays you, and that’s it. But every book sold puts more money in your pocket, forever. Which means a hit movie or series will make you far more money in book sales than you’ll ever get from Hollywood—even if they pay you $5M.

Synergy: Having both a screenplay and a book gives you two different properties, which can be sold to two entirely different markets: publishers (or readers) and Hollywood. Interest from publishers can be used to ratchet up interest from Hollywood, and vice versa. The effect is amplified when there’s an offer, and amped again if there’s a sale. Best-case, you (or your reps) can play on this to spark a bidding war for book and movie. Even if you’re going indie with the book and there is no trad publisher, it can’t hurt to stamp “Soon to be a major motion picture [or series]” on the cover.

Aside from all that, the very process of adaptation forces you to think of new ways to approach the story. The book may be 300 pages. It may be 500. The script will be 120 or less. Nonessential elements must be cut. Something that took 50 pages to play out in the book, might now play out in five. How do you do that? Maybe characters A and B can be combined to speed things up. And so on. You (or your screenwriter) are compelled to think up new ways to convey the same story—things you never would have thought of before, because you didn’t have to. Almost invariably, some of those things can then be used to improve the novel. So there’s creative as well as financial synergy, or cross-pollination, at work.

Cons

Timeline: You can indie publish your book in a day, and trad publish in 12-18 months. A movie or series season might take a year to get made. Or five. Or more. It depends on who gets involved, how committed they are and/or how much money and power they can bring (or attract) to the project.

Control: Hollywood doesn’t pay what it does in order to have you tell them what to do; Hollywood pays well so they can do what they want to do. Maybe that means filming the screenplay just the way we wrote it, maybe it doesn’t. Unless you’re J.K. Rowling or Stephen King, you’re not likely to have much say in the matter. The best you can do is sell it to someone who sees the story the same way you do.

All-or-Nothing: You can pitch your book to trad publishers and—if you don’t get an offer you like—go indie and publish the book yourself. If a screenplay doesn’t sell, you’re unlikely to be able to go and make the movie yourself, simply because the process is so costly. Unless, of course, you’ve got a really low-budget project. That said, if the book succeeds, it can resurrect interest in the screenplay—and vice versa.

Speculative Nature: Like books, screenplays and series proposals are inherently speculative ventures. They are written “on spec,” and offered for sale. There are no guaranteed sales, and anyone who tells you otherwise is not being, shall we say, entirely forthright. Most screenplays—like most books—do not sell, and for the same reason: most are dreadful. And sometimes, as with the first Harry Potter novel, even good works get multiple “passes.” The only real guarantee is this: The better the screenplay, the better your chances. You can’t win if you’re not at the table.

Time or Money: Creating the adapted screenplay is going to require time (if you do it yourself) or money (if you have some else adapt the book for you). If you have more money than time, the effort on your part will be minimal; if you have more time than money, it’s going to take a while to get everything right, because you’ll be working in an unfamiliar medium, with unfamiliar demands and industry expectations.

Three Paths to an Adapted Screenplay

Once you’ve made the decision to adapt your book for the screen, the path you take to get there very much depends on your reason for wanting a screenplay in the first place, and the amount of time (and money) available. These paths boil down to: Do it yourself, Do it with help, and Have someone else do it for you. Let’s explore each in a little more detail…

Adapt Yourself: If you plan to make a career out of being a screenwriter, this makes sense, and you might as well start now. The pros of this approach are mostly about cost and control. You alone will determine the content, including every nuance of plot, character and dialogue—right down to the placement of commas and periods. The script is going to be exactly what you want it to be, and no one (not yet, anyway) can tell you any different. And, of course, doing it yourself means you don’t have to pay anyone else to help.

The cons of this approach mirror the pros. The cost—in terms of time spent—will be high, perhaps enormous. If your learning curve is fairly typical, you’ll be at it for three to ten years before your screen-side work is good enough to catch the eyes of agents, managers, and buyers. Working solo and making all decisions in a vacuum may well lead you to make mistakes that render the script unsellable. Meanwhile, you don’t even realize there’s a problem. Hollywood’s priorities are unique to the industry, and many of them are meaningless to publishers, trad or indie. (“How much will it cost to film this page? Will an A-list actor want to play this role? Can we find a location with better tax incentives? How will this play in China? Can we put it on a lunchbox, or is this Oscar material?” And so on.)

The writing approach is also very different. Books excel at rich detail and depth, and often dwell inside the characters’ heads. You can run a scene for twenty pages, if you keep it interesting. Screenplays are all about conveying maximum impact with the fewest number of words. Film itself is limited to portraying things seen and heard by the audience; if you can’t point a camera and a microphone at it, why bother?

At the same time, the abbreviated writing style of the script still has room for creativity on the page. You’re expected to powerfully convey things that are internal, in a way that helps the director and cast externalize them so they can be filmed. For example: “The flame reveals the face of JACK WALSH. Strong. Haggard. A killer stare. Pressure-cooker of a man. Always about to explode.” (From Midnight Run, by George Gallo.) The audience will never read that description—but those qualities will be brought to life by actor and director.

Simply put, pretty much everything that makes for a great author, also makes for a lousy screenwriter, and vice versa. Some writers have mastered both forms; most have not because they can’t, or they’re not interested, or they’re unwilling (or unable) to put in the time it takes to do so. But if this is a career path for you, it must be done.

If, on the other hand, you’re not looking to become a professional screenwriter, and all you really want to do is get this particular story on the screen—then learning to write screenplays is a bit like building your own jumbo jet because you want to get to France. It’s a whole lot easier to just buy a ticket. Before we get to that, though, let’s explore option number two…

Adapt With Help: Door Number Two is doing the adaptation yourself, with guidance from someone who already knows the territory, so to speak. (Preferably someone with a foot in both worlds—books and screenplays—so they know where you’re coming from.) The pros here are obvious. Real-time feedback and creative input from an experienced screenwriter will (if you heed their advice) help you avoid common pitfalls you didn’t know were there. It will speed up your timeline, potentially saving you years of misguided (or unguided) effort. You’ll still control the placement of every comma. And you should—again, provided you heed good advice—wind up with a much better final draft. Finally, this option will (probably) cost less than hiring someone to do the adaptation for you.

The cons are that this obviously costs more, moneywise, than doing it yourself. It may or may not cost less than hiring someone to adapt for you, depending on how fast you climb the learning curve. If everything goes smoothly, and you’re on the mark most of the time, this will be a less-costly option. If the shift to this unfamiliar format with its attendant demands doesn’t come easily, and things go into endless revisions because of that—this could actually turn out to be the most costly way to do things. And you won’t know until you’re well into the process. Now for Door Number Three…

Hire A Screenwriter: The third option is just that: hire someone else to do the adaptation for you. Preferably someone who writes books as well as screenplays, and knows their way around an adaptation because they’ve done it before. This is the express lane, and that’s one of the pros: there’s no learning curve to deal with, so the screenplay will be ready in a fairly short period of time. Those pesky pitfalls will have been avoided, and the screenplay will be better and more salable than anything you could have written yourself in any reasonable amount of time. As a bonus, nothing teaches you more about screenwriting, faster, than seeing the craft’s core principles applied to your own work.

The first con here is that you’re no longer controlling every scene, sentence, and comma (if that’s important to you). On the other hand, you and the screenwriter can (and should) check in every thirty pages or so to make sure everyone’s happy with the way things are going. And you (or your writer) can always tweak things later. (Whether that’s advisable is another matter.) The other con is cost. Good help doesn’t come cheap, and a screaming bargain by Hollywood standards is still a significant amount for most.

You’ll find good writers for a fraction of this cost, but for purposes of comparison, the current WGA (Writers Guild) feature screenplay minimum hovers around $130k. No Guild member can sell a screenplay for less than that minimum. There is no maximum, and some writers routinely charge a million a script. Again, it’s possible to find a good adaptation specialist—one who’ll keep the heart of your story alive and beating strongly in its new home—for a fraction of that first figure. Though, as always, beware the deal that seems too good to be true, because it probably is.

That’s a sort of whirlwind tour of the basics. If you’d like to know more about what The Editorial Department can do to help with your own story-to-screen journey—from consulting to writing the adaptation itself—give us a call at (520) 546-9992 or send us an email. You’ll find some basic screen-side services listed here.

Article copyright © by John Robert Marlow – All rights reserved.