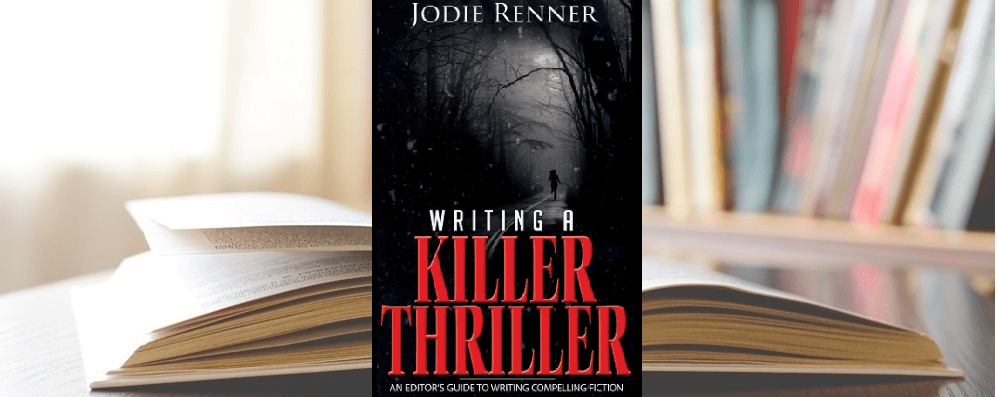

In Writing a Killer Thriller, Jodie Renner covers all the elements necessary to create a compelling thriller. Clearly structured and easy to read, with examples from popular novels and movies, Writing a Killer Thriller offers a wealth of important information for the new (thriller) writer and can serve as a helpful refresher and reference book for experienced authors.

Content & Organization

Divided into nine parts, Writing a Killer Thriller starts by explaining the difference between thrillers and mysteries and exploring the basic ingredients of a great thriller. Those are covered in more detail in the following chapters. Part I also gives tips on how to come up with intriguing plot ideas.

Part II is dedicated to designing the plot. It explains approaches to story structure that can be used to craft an engaging thriller—the mythic structure, the three-act and the five-act structure, and the eight-point story arc. It also lists possible big-picture problems concerning structure and plot and how to solve them.

Part III takes a closer look at the attributes that make characters compelling, while differentiating between hero and villain.

Part IV is about tension and conflict. Renner thoroughly dissects the components of a gripping opening and, for each of them, includes examples from bestselling novels. Two helpful lists of typical amateur mistakes that weaken the opening pages or the whole story can also serve as troubleshooting tools for already-completed manuscripts. Renner continues by explaining the importance of tension on every page and by offering detailed advice and suggestions on how to create it—on both story and scene levels.

Part V is again dedicated to the characters—this time on how to bring them to life on the page through a deep point of view (close third-person point of view from inside the hero’s mind) and by using the “show, don’t tell” principle. Both enable the reader to experience the story through the protagonist’s eyes, and any writer of commercial fiction should familiarize themselves with these highly effective techniques.

Part VI considers the importance of sustaining the suspense throughout the novel and introduces techniques to help accomplish this. Renner covers foreshadowing, withholding information, delaying the unveiling of critical details (and thus reader gratification), stretching out tension, character epiphanies, and revelations in great detail. She also addresses the characteristics of a nail-biting story climax and a satisfying ending.

Part VII deals with the revision of a manuscript with respect to style, pacing, and structure, on both story and sentence levels. It includes many examples that illustrate Renner’s tips.

Part VIII gives an overview of the essential elements of a bestselling thriller and offers a checklist for ratcheting up the tension and suspense. Both are great tools that recap the most important components of a thriller and help spot weaknesses within a manuscript.

The book ends with a glossary of fiction terms, an explanation of thriller subgenres with examples, and a collection of resources for thriller writers, including books, organizations, conferences, conventions, and workshops.

The Takeaways

Great thrillers are carried by complex characters

Both hero and villain need to be complex and multidimensional—the hero even more so than the villain. The hero has to be charismatic, clever, skilled, determined, and courageous, but also come with some baggage and human flaws to make him relatable to the reader. The villain has to be a worthy opponent who is at least as smart, determined, and tough. He should be truly nasty and evil, but he needs to have his reasons and personal justifications for his actions. It is possible but not necessary to also make him sympathetic.

Great thrillers are built on a solid structure

Drafting a rough outline before starting to write the thriller helps to focus the plot and prevent it from meandering. The outline should include the most important events, which need to be connected by cause and effect.

While there are several ways to structure an effective novel, the three-act structure is the most popular one:

Act I (= the Beginning)

Act I covers about a fifth or sixth of a thriller. It contains the hook and setup, introduces the hero and villain, and includes the inciting incident. It needs to be full of complications, tension, and intrigue to grab the reader from the start and not let go. At its end, the hero is confronted with a difficult decision, which leads him (or her) to the second act.

Act II (= the Middle)

Spanning around half of the story, Act II is where the problems, stakes, and tensions continually rise. To deal with the challenges, the hero must grow as a person. Before its end, a turning point—be it a revelation, crucial discovery, or a major setback for the hero—sets up the final battle that takes place in the final act. It leaves the hero no choice but to carry on.

Act III (= the Ending)

In Act III (the last quarter or fifth of the thriller), the hero faces his greatest challenge and, in a heart-pounding climax, just barely manages to defeat his opponent.

Great thrillers allow the reader to experience the thrill together with the hero

For maximum reader involvement, novels should be written in close third (or first) person point of view. This deep point of view helps the reader become one with the protagonist: It allows them to experience the story through the hero’s eyes and other senses, through his emotions and reactions. To achieve this, the author must become the viewpoint character—seeing, feeling, and knowing only what the character does—and express the way the character would. If the story is alternatingly told from the viewpoint of the hero and the villain, more time should be spent with the hero so readers won’t lose their connection with him.

Readers are also sucked into a fictional world by the “show, don’t tell” technique. This means letting all crucial events take place in real time, conveying dialogue, action, reaction, and the viewpoint character’s thoughts, feelings, and sensory impressions. The first few pages of a thriller should always show, not tell. Unimportant scenes and transitions, on the other hand, should be summarized if they can’t be skipped altogether.

Great thrillers are made up of great scenes

Each scene

- needs tension, conflict (be it external or internal), a mini-climax, and change

- should end with more problems for the hero or with a cliffhanger

- has to bring the hero closer to or farther away from his goal

Action scenes should be interspersed with quieter scenes to vary the pacing and level of tension and offer breathers.

Great thrillers captivate the reader from the start

The first paragraph needs to hook the reader. An absorbing opening comes from

- immediately introducing the protagonist (who) by writing from their viewpoint and, as soon as possible, showing what drives them and what their weaknesses are

- being clear about what is happening

- being clear about where it’s happening and when

- showing these details to the reader, not telling them about them

- making sure your scenes are marked with tension and conflict (readers can faster connect with the hero if he is dealing with some inner or outer conflict from the onset of the story)

- introducing a second character quickly so the hero can interact with them in real time

- making sure the villain appears within the first two chapters

The beginning also needs to establish the tone, mood, and style of the entire novel.

In great thrillers, the tension keeps tightening

The tension from the opening has to be followed by increasing tension and conflict on every page:

- The conflict needs to be real, between two people with opposing goals, and not brought about by bad luck or adverse fate. It has to personally threaten the hero or his loved ones.

- The hero has to end up in a situation that leaves him no choice but to stay and fight (the crucible or cauldron).

- The conflict has to be layered and complex. It needs to twist, turn, and escalate.

- The stakes need to continually rise, forcing the hero to confront and defeat his deepest fears and develop his inner strength. He has to be challenged to the maximum, using his brains and drawing on his physical and psychological resources to overcome the conflict and defeat the villain.

- Obstacles and complications that cross the hero’s plans and lead to setbacks amp up the tension, as do turning points and dilemmas, surprises and reversals.

- Time constraints or some kind of “ticking clock” device will help to increase the pressure.

- Tension also needs to be palpable during interactions between supporting characters.

Great thrillers keep readers hooked with the help of structural and other devices

Structural techniques to increase the tension:

- Chapters and scenes should “start late and end early.”

- The higher the tension, the shorter the chapter, scene, and sentences should be. Longer sentences, scenes, and chapters go along with a more relaxed mood and slower pacing.

- Most chapters and scenes should end with a cliffhanger—for example, a shocking (or at least surprising) revelation, setback, threat, or unresolved conflict.

- Cutting scenes or chapters short by jumping to another scene during a gripping moment is an effective way to keep readers engaged.

Suspense can be increased by building anticipation and apprehension through

- subtle foreshadowing: hinting, for example, at future trouble or relevant secrets in the main characters’ pasts or divulging character traits that will make later actions believable

- delaying the revelation of significant information by:

-

- disclosing it little by little in fragments during the story

- going into slow motion by showing all the critical details (including feelings) during pivotal scenes

- adding distractions and interruptions in such scenes

- using the setting to heighten suspense and create a specific mood

Great thrillers include jaw-dropping twists, a breathtaking climax, and a satisfying ending

While twists need to be unexpected, they also have to be plausible. A thriller should include two major twists—one in the middle and one at the end.

The protagonist should experience at least one epiphany (enlightening realization), ideally in the middle of the story, causing him to grow in character and provoking a turning point in the plot.

The story climax needs to be the scene with the most tension, conflict, and suspense—and the highest stakes—of the entire novel. Challenged to an extreme, the hero will triumph in the last moment.

In a satisfying ending, the hero’s major problems and the main story conflict should be resolved and the people closest to him safe, but he may have had to accept some smaller defeats. Adversity has led to a positive change in his character.

Closing Thoughts On…

The structure and contents of the book

I like that the advice in Renner’s book is clearly laid out with lots of white space, subheadings, and listings with keywords marked in bold. It includes quite a bit of overlapping information and repetition, though, which should have been cut or condensed. I would also have found an index helpful.

Using a formula for writing thrillers

Renner recommends a very formulaic approach to writing thrillers. There are certainly quite a few successful thrillers out there that keep readers on the edge of their seats by following said formula. Yet if you have read several of them or are familiar with the underlying structure and requested elements, they can become rather predictable and obvious—even though including unpredictable twists is part of the required components.

The book also offers a blueprint for writing effective scenes. Yet planning your story in such detail may take the joy out of writing—especially if developing a story is a deeply emotional process for you.

If you’re looking for a formula to write page-turning genre thrillers, this is the book for you. If you prefer a more individualized approach, it can serve as an orientation with lots of useful advice. In my opinion, how closely you follow the recommended formula should depend on what works best for you as a writer. For some, the required elements may feel like a safety net, while to others, they might feel restrictive. I dare say, though, that even if you go about planning and writing your thriller in a less rigid way, many of you will intuitively end up with a storyline resembling the one proposed in Renner’s book.

The necessary characteristics of the hero

Renner concludes that the protagonists of successful thrillers need specific qualities that almost make them seem superhuman. It’s definitely fun to experience a story through the eyes of someone blessed with a combination of skills and talents that most of us can only dream of. But couldn’t a thriller be just as compelling with a protagonist who is more like us?

For example, according to Renner, the hero should be experienced and can’t be timid. Yet timid and inexperienced people also need to react when threatened, and they’d end up going through an even more pronounced character arc than somebody with the opposite traits.

Renner states that the hero needs to be physically fit to be able to handle the respective challenges he’ll encounter. How about having a handicapped hero outsmart the villain?