[by Ross Browne]

One silver lining to the challenges of the writing life in 2020 is the growing number of popular authors doing online events with their fans. This gives us the opportunity to get up close and personal (if only virtually) with some of the biggest names in publishing, and in many cases pose questions to our favorite authors directly.

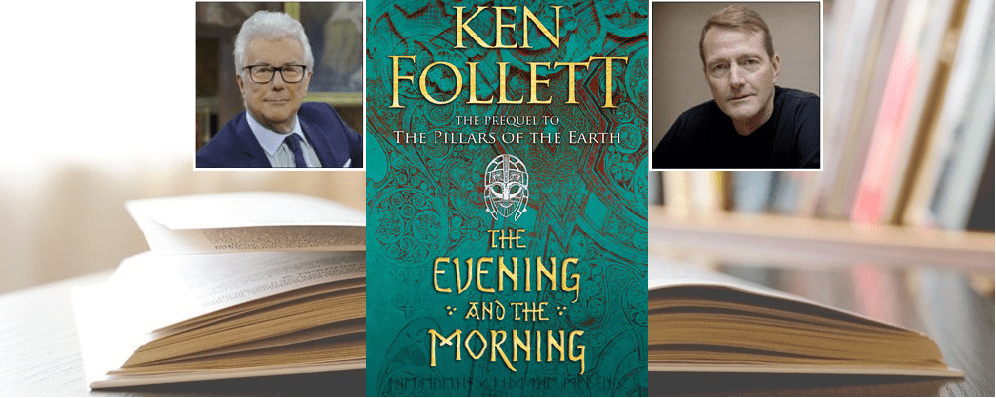

When we saw Ken Follett and Lee Child were teaming up for such an event, our own Ross Browne jumped at the chance to join in, listen to what they had to say, and pass along some insights from their discussion that we hope you find useful.

A Welshman, an Englishman, and over a quarter-billion books sold

With more than 260 million copies of their books in print, Follett and Child have had extraordinary careers. What a treat it was to listen in as these delightfully humble literary superstars shared thoughts on writing, publishing, and where their stories come from.

The jumping-off point for this live-streamed conversation was the release of Follett’s newest novel, The Evening and the Morning, which is a prequel to the wildly popular (and utterly brilliant) Kingsbridge trilogy, released between 1989 and 2017. The Evening and the Morning takes readers back three hundred years before The Pillars of the Earth, the first in a series that might have never been (more on that shortly) and without a doubt one of the most successful historical novels ever written.

Set at the end of the Dark Ages, when England is under attack by both the Welsh and the Vikings, the novel is described by the publisher as “an epic journey into a historical past rich with ambition and rivalry, death and birth, love and hate, that will end where The Pillars of the Earth begins.”

Follett spoke at some length about how the series came to be and what he set out to accomplish with it. Though a moderator for the event rather than the headliner, Lee Child, a personal friend of Follett’s and, of course, an ace writer himself, had plenty of interesting observations to add to the mix. Here are the juiciest takeaways for writers who share our admiration for what these two mightily talented authors do so very, very well.

There’s no team in Follett

If you’ve read any of the Kingsbridge trilogy you know how complex, ambitious, and exhaustively researched these books are. It’s no surprise Follett often encounters suspicion that he surely can’t be doing this alone, that he must have a team helping him write, or at least research, these epic tales. And some wonder if some sort of mystical muse might also be at work, helping him dream up these stories and make them so engaging.

Follett is quick to dispel both notions. This is a writer who has never experienced writer’s block yet does not believe in muses or anything magical or mysterious when it comes to inventing his stories. He credits instead his own imagination, a diligent work routine, and a restless creative spirit that draws him to a broad array of settings, circumstances, and events on which his books are based. He’s an avid reader of history, always on the lookout for where good fictional stories might lurk in real-life conflicts of the past. While he does get vetting for factual accuracy from experts on pertinent topics, he does all his own research and all his own writing. The motivation to take on this sometimes colossal task usually stems from his own curiosity about something he thinks readers might find interesting.

An unexpected seed of a groundbreaking novel

With The Pillars of the Earth, it was the author’s fascination with cathedral architecture that compelled him to write the story. Though now an atheist himself, Follett grew up in a religious household where he encountered a starkly puritanical interpretation of worship. Services took place in a “hall” rather than a church, and in these places renderings of Jesus were forbidden. Decades later, Follett took a keen interest in what was happening on the other end of the spectrum, with these gigantic, highly ornate monuments to God that took hundreds of years and incalculable amounts of money to build. He recalls wanting to learn everything he could about who built these amazing structures, why they chose to do so, and how they did it. His effort to satisfy his own curiosity led to three years of work and a massive manuscript completely unlike anything he’d written before.

Panic at the publishing house

Surprisingly—or perhaps not—many involved with publishing Follett’s work were not happy to learn of this. Enough so that someone cornered his wife and begged her to make him stop writing The Pillars of the Earth. The fear was that a book so different from what his readers loved and expected would ruin his career.

In hindsight, this seems shortsighted if not downright foolish. But Follett’s story about this didn’t surprise Lee Child one bit, who talked a bit about the immense pressure popular authors often face from their own publishers to stay in their lanes and keep producing what readers have proved willing to buy in great numbers. Child is, of course, a veritable poster child for success with this model, having written twenty-five consecutive books in his Jack Reacher series without any sidesteps or literary dalliances.

Many writers don’t realize how wildly speculative the publishing business is. Editors are continually paying advances for books they have no way of knowing will actually sell. For every Ken Follett or Lee Child novel a publisher puts out in a given year, there are many other titles that may sell well, modestly, or only to the author’s relatives. This is why publishers rely heavily on their flagship authors and may freak out a little bit when they start taking risks and writing in different genres. Child points out that their “known quantities” are vital to publishing projections, budgets, and balance sheets—all the good things that keep the doors open and the lights on.

So when Follett, a writer who had become a household name writing 20th-century spy thrillers, showed up with a thousand-page novel about a stonemason who dreams of building cathedrals, it’s no surprise that there was some rather grave concern. But Follett had himself worked in publishing and believed, rather fervently, that a very good story could be made out of building a cathedral. He confesses to having some doubts about his own ability to pull it off, but he believed the premise held the potential for a popular novel, which is exactly what he was trying to write. The last thing he wanted was what his publishers probably feared most: a “difficult” novel that would challenge readers and perhaps win awards but not sell like Ken Follett.

He stood his ground, his publishers eventually relented, and The Pillars of the Earth became a huge worldwide success. (“We got away with it!” Follett said with a wry smile.) Two sequels and now a prequel later, we can all look back and savor a lesson in why trusting your instincts and writing the book that’s in you is so often a good idea. And why sometimes the best thing a publisher can do is simply step out of the way and let that happen.

A new comfort zone for Follett and his readers

Part of the reason for the series’ success is Follett’s rather remarkable feel for the Middle Ages and his skill in bringing this particular period to life so well. When asked why he chose to dwell in this era, Follett pointed out how hard life was in this time and thus how many opportunities there are for compelling stories. People were generally hungry and cold, living in a ruthlessly violent world where there was often no justice, no medicine, and no cause for hope. It was a dreadful time in many respects, and one he thinks readers should enjoy reading about, in part because it makes us appreciate the twenty-first century comforts most of us might otherwise take for granted.

Child pointed out the natural fascination readers have with a period in which law, order, politics, and societal structure couldn’t be taken for granted. This was a time when freedom wasn’t a right but something much more elusive that often had to be fought for. The fight for freedom is something Follett writes about often (usually via stories of very strong female characters), in part out of fascination with how we got to this point where more people enjoy freedom than ever before.

“How did we get be to so lucky?” he asked rhetorically. What happened to allow a part—a regrettably small part—of the modern civilized globe to be free and prosperous? One thing that interests him is the battles (literal and figurative) people fought to achieve freedoms. There are great stories, both real and imagined, lurking in these efforts. And Follett has mined gold from them in his work. I personally believe that one reason he’s been so successful in doing this is the deep and heartfelt compassion he exhibits for the characters involved in this struggle. He may be one of the most successful authors on the planet living a cushy life in an era of creature comforts, but he writes as if he knows firsthand what it’s like to be freezing, starving, and completely desperate in a time where there was often nowhere to turn but toward death as a release. His empathy for his characters is rather extraordinary, and that’s part of what makes his stories so irresistibly engaging.

Die Nadel!

Follett’s success with the Kingsbridge series was surely in no small part indebted to the impact he made over a decade before with Eye of the Needle, one of the most successful spy thrillers ever published. This is a novel that Child recalls being asked to read by his agent when Child encountered some trouble managing suspense in his first Jack Reacher novel, Killing Floor. The suggestion came as no surprise. Child had read the book and believes Eye of the Needle to be a veritable textbook on writing suspense.

He read it again and presumably came away with insights to help address the problem and make his debut title a hit, thereby opening the door to dozens more books in a series that has sold more than one hundred million copies. I think this story makes a good case for why any author writing suspense fiction should read Follett’s masterpiece. (Which, by the way, he wrote in three weeks at the age of twenty-seven. Writing that book “was like running downhill,” he said. “The ideas just came nonstop.”)

So Eye of the Needle inspired Lee Child. But what about Follett, one attendee asked. What books inspired Ken Follett? What put him on the path to becoming a literary superstar?

Bond…James Bond

One such book, it turns out, was Ian Fleming’s Live and Let Die, the second in his iconic James Bond series. This was a book that got Follett asking some questions I believe all writers should consider carefully. What experience am I trying to create in this story? What do readers really want? What are they looking for in the bookstore as they peruse covers, flap copy, and the first few pages?

One answer, in Follett’s view, is a “wonderful experience.” Not something ordinary but something exceptional that will transport the reader. Follett reminisced fondly about how he as a teenager felt about those James Bond stories and the “sheer joy” of having a new Bond book in his hands. That delight, that glorious sense of anticipation at starting a new book from an author you love, is what he tries to create for his readers with every novel.

And that’s perhaps the best takeaway of all for any writer, especially for novelists. If you approach your work with the intent of cultivating for readers this joy, this pleasure, this rabid sense of anticipation for your next book, your odds of success will improve dramatically.

How do you do that? There’s no magic formula, of course, but here are some tips I was able to distill from the discussion.

- Always be on the lookout for fertile ground for your stories, but don’t rely on the intrinsic interest of period or setting to create engagement. The story itself needs to be seriously compelling, often a struggle for something that seems impossible or against something that seems inevitable. Pay close attention to the stakes of the story, what’s really on the line, and why it matters to your characters.

- Recognize that most things readers really are concerned about in their own lives—marriage, work, money, family, war, violence—are universal and change very little, even over centuries. If you write well about such matters and weave them into your stories, that helps readers relate to what you’ve written.

- Consider the big-picture objectives of your characters, why they’re doing what they’re doing, why their actions matter in the greater scheme of things. (“Spies shouldn’t be spies just so they can get in fights and seduce women,” Follett said.)

- Work ethic is important. Follett said his process is as simple as sitting at his desk and spending all day writing. This is what he’s done for forty-five years now, and that predictable, systematic approach has clearly served him well. Some successful writers work from early morning until noon, others in the wee hours. Whatever your schedule, do your best to stick to it.

- If you’re writing about real-life historical events, be glad you live in the age of the Internet and do your research thoroughly. It’s important to get your facts right.

- Try to approach physical description in a way that doesn’t just describe something or someone but makes an emotional impact on the reader.

- Be careful with exposition. Use it sparingly and place it smartly, ideally after readers have become curious about the topic being explained. But don’t underestimate its importance. Don’t overlook the fact that many readers like to learn from novels, not just be entertained. (More on this topic is available at https://www.editorialdepartment.com/lee-child-jack-reacher-handling-exposition/.)

- Strive to write in a way that cultivates interest in things that might not immediately appeal to readers outside the context of the story.

- Finally, think carefully about your target audience, what you think they want, and what your story delivers. Think carefully about what you expect readers to respond best to. Don’t stop revising until you believe you have a novel that will knock their socks off and leave them rabid for your next one.

The broadcast of this conversation is available for members at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZX41mzhFXHw&feature=youtu.be, and very much worth the hour or so it takes to watch it. Ross left the session brimming with admiration for both these authors and a keen sense of gratitude for what they shared.